The War Within: a soldier’s plea

Darren watches as the faces of friends fade in and out, his breath slow and ragged. He finishes off another beer and puts the can down next to an empty bottle of Jack and the nearly finished 24 pack. A bottle of pills the doctor gave him, sit on the other side. Darren doesn’t remember how many he’s taken tonight. He doesn’t want to remember, doesn’t want to see the images again.

The nightmare begins nearly the same. Men huddled against a building, rifles in hand, fingers lightly on the triggers. The order comes to advance; each man takes slow, cautious steps forward. Darren can hear the echoes of rifles going off in the distance. The earth shakes from a bomb hitting a building nearby. He looks back to see a new replacement looking around, scared. He offers a gesture of encouragement; he vaguely remembers what it was like to be green, the first time out. Funny how 8 months can make such a big difference. The group is able to advance for two blocks before they’re commanded to halt. Before anyone can move a burst of bright lights, flying debris and the ground shakes again. The building next to them collapses. Rifle fire and commands fill the air. His mind becomes blank for a moment, just a second. He turns to find one of his friends, McFarson, lying on the ground, his face nearly gone. His head snaps to when he hears his name and a command to get moving. He starts ahead, only to remember the green replacement. He looks around to find the kid in pieces on the opposite wall. He gathers what encouragement he can find and moves closer to his commanding officer. Five of the 12, which started out, survived that day.

Darren looks down at his leg; his pants cover the wounds from the debris. The doctors say he was lucky. The wounds were only minor. “Lucky?” he retorts. “Lucky would have been dead with the rest, lucky is not coming home and losing your wife and kids. Lucky isn’t having people look at you funny and call you baby killer when you walk the streets. I can’t even remember why I was so proud to wear the uniform.”

Darren wakes up, only to find himself, not at home, but somewhere strange. He’s mind is in such a state that he really can’t focus to react. The nurses are all nice. The others that live there are a bit strange, but Darren’s mind is still to sedated to care.

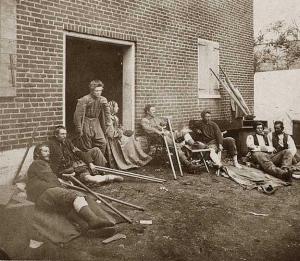

Scenario sound familiar? It is a combination of many stories written by soldiers since the Civil War.

Flashbacks, nightmares, depression, anxiety, removing yourself from activities you once enjoyed, becoming emotionally numb and difficulty maintaining close relationships are just some of the symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

The Department of Veterans Affairs Center for PTSD defines PTSD as: a psychiatric disorder that can occur following the experience or witnessing of life-threatening events such as military combat, natural disasters, terrorist incidents, serious accidents or violent personal attacks.

Today, more than 150,000 veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have been officially diagnosed with PTSD. The number likely is higher because of the stigma attached to the disorder and also because some service members have sought out private treatment rather than through the Defense Department or Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) (Knickerbocker).

The US history of taking care of her mentally wounded soldiers:

Richard A. Gabriel, a consultant to the Senate and House Armed Services Committees and one of the foremost chroniclers of PTSD, tells us that in 1863 the number of insane soldiers simply wandering around was so great, there was a public outcry. Because of this, and at the urging of surgeons, the first military hospital for the insane was established in 1863. The most common diagnosis was nostalgia. The government made no effort to deal with the psychiatrically wounded after the war and the hospital was closed. There was, however, a system of soldiers’ homes set up around the country (Bentely).

Richard A. Gabriel, a consultant to the Senate and House Armed Services Committees and one of the foremost chroniclers of PTSD, tells us that in 1863 the number of insane soldiers simply wandering around was so great, there was a public outcry. Because of this, and at the urging of surgeons, the first military hospital for the insane was established in 1863. The most common diagnosis was nostalgia. The government made no effort to deal with the psychiatrically wounded after the war and the hospital was closed. There was, however, a system of soldiers’ homes set up around the country (Bentely).

During World War I, military officers encountered a new and puzzling phenomenon: soldiers emerged from the trenches stuttering, crying, trembling and at times were even paralyzed and blind. Those in charge were convinced these soldiers were cowards or malingerers who deserved stern discipline or to be court-martialed (Pols).

By World War II, psychiatrists were attached to many military units at the division level. Soldiers who were traumatized by witnessing extreme violence were pulled out of the front lines for treatment. This involved supportive counseling with the aim of getting them back to their fighting comrades within three days to a week (Taylor).

Repeated and extended deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan are driving psychological injuries upward, say military and civilian doctors, despite a spectrum of new government programs aimed at preventing and treating them.

With the advent of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Army started programs to teach soldiers how to identify signs of PTSD, prepare mentally for combat, and remove the stigma of seeking help (Carroll).

Through trial and error, they’ve found that antidepressants help calm soldiers down enough to stay and finish their tours(Vogt).

Tricare is the military insurance company that the government has put in place. According to their brochures and website:

If you’re seeing a mental health counselor, licensed professional counselor or pastoral counselor, you must have a written referral from an M.D. or D.O. and the care must be supervised by a physician. Does the M.D. Or D.O. know who they are referring the person to?

So who are these mental health care providers?

Out of the course listings from the top ten psychology colleges in the US only one has a specialized seminar that is specific to PTSD. None of the schools offer courses in dealing with military personnel beyond treating depression, anxiety and sleep disorders. If the issue of combat PTSD so prevalent, why is it not a main focus in teaching current and future mental health care providers?

According to the National Conference on Ministry to the Armed Forces website:

The basic requirements to become an Active Duty, Reserve, Guard or Civil Air Patrol Chaplain include: Ecclesiastical endorsement (certifies experience and degree requirements meet the standards of the respective ecclesiastical group). Two years religious leadership consistent with clergy in applicant’s tradition (strongly recommended). A graduate degree to include a minimum of 72 semester hours (or equivalent) from a qualifying (accredited) institution. Not less than 36 hours must be in theological/ministry and related studies, consistent with the respective religious tradition of the applicant. Endorsers are free to exceed the DoD standard per ecclesiastical requirements, but cannot go below the minimal DoD requirements, e.g. many endorsers specifically require the Master of Divinity degree. Pass a military commissioning physical. Pass a security background investigation. Ability to work in the DoD directed religious accommodation environment. It does not state that these counselors should be trained in counseling for post-traumatic stress.

The basic requirements to become an Active Duty, Reserve, Guard or Civil Air Patrol Chaplain include: Ecclesiastical endorsement (certifies experience and degree requirements meet the standards of the respective ecclesiastical group). Two years religious leadership consistent with clergy in applicant’s tradition (strongly recommended). A graduate degree to include a minimum of 72 semester hours (or equivalent) from a qualifying (accredited) institution. Not less than 36 hours must be in theological/ministry and related studies, consistent with the respective religious tradition of the applicant. Endorsers are free to exceed the DoD standard per ecclesiastical requirements, but cannot go below the minimal DoD requirements, e.g. many endorsers specifically require the Master of Divinity degree. Pass a military commissioning physical. Pass a security background investigation. Ability to work in the DoD directed religious accommodation environment. It does not state that these counselors should be trained in counseling for post-traumatic stress.

On 24 March 2010, members of the US Senate, Subcommittee on Personnel, and Committee on Armed Services gathered together to discuss the mental health care currently being issued to military personnel. The following quote is the statement of RADM Christine S. Hunter, USN, Deputy Director of Tricare Management Activity:

Our efforts to reduce the stigma associated with seeking mental healthcare have been accompanied by an increase in providers to meet the growing demand. Together with the Surgeons General and our TRICARE contractors, we’ve added over 1900 providers to the military hospitals and clinics, and more than 10,000 added to the networks. Visits have increased dramatically, with 112,000 behavioral health outpatients now seen every week. In addition, service members and their families can access the TRICARE Assistance Program for supportive counseling via Webcam from their homes, 24 hours a day. (United States Senate Armed Services Committee).

Obama said his fiscal 2010 budget, which includes the largest VA funding increase in 30 years, will help to confront PTSD and traumatic brain injuries in a “more robust way.” “Throwing money at the problem by itself is not enough,” he conceded. But, he added, money does help by funding more counselors, mental health specialists and treatment facilities. “We’re hiring mental health providers,” Shinseki pointed out. “We’re up to 18,000 in the VA today (Obama, Shinski).”

Tricare refused to comment on the criteria in which these mental heath care providers are contracted.

If schools are not training psychologists and psychiatrists to help those with PTSD, instead of treating the anxiety, depression and sleeplessness it causes, then why is the US Government contracting and referring these professionals to US military personnel?

The Golden Hour – a time stamp of saving the soul

R Adams Cowley, M.D., explained in an interview: “There is a golden hour between life and death. If you are critically injured you have less than 60 minutes to survive. You might not die right then; it may be three days or two weeks later — but something has happened in your body that is irreparable.”

But is there a “Golden Hour” for those that are injured mentally?

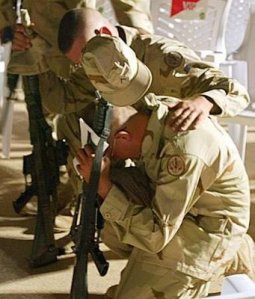

Civil service agents, depending on departmental protocols, are removed from service to meet with a psychologist/psychiatrist after being involved with a shooting. Soldiers serving on the battle front do not have that luxury. They go through suicide and depression briefings before they are deployed and when they reach the country, in which they are deployed. Though most are never introduced to the mental health care provider or counselor. The soldier is left to their own conscious to seek mental health care support. Once care is granted most do not have immediate access to the provider. Some only see the provider once a month, when the provider makes the tour to the base or camp. There is no mandatory protocol that states that a soldier must meet with a mental health care provider or group therapy session after any mission.

Speaking to commanding officers and non-commissioned officers if they are told that a soldier is feeling or showing suicidal or depression tendencies the soldier is put on suicidal watch and then taken to medical professionals. When deployed, if military personnel has issues with a situation there are psychologists, psychiatrists and pastoral counselors to help. When speaking to the soldier, most say that there is no professional help, save medical doctors or pastoral counselors, to talk to. Most soldiers do not seek help due to the stigma of having a mental disorder.

Medicating soldiers in war brings up a host of difficulties not faced by doctors back in the States. The brigade psychiatrist, Dr. Randal Scholman, said he finds himself making more informal or nontraditional diagnoses. Deployed soldiers are in a particularly stressful environment, and often it’s hard to tell if a problem is temporary, he said.

The most common drugs he prescribes are sleeping pills, followed by antidepressants. Often, he gives a soldier Prozac or Paxil to treat what he and his colleagues call “combat operational stress reaction.” The disorder — which is not formally recognized — includes symptoms like sleep problems, irritability and propensity to anger. Soldiers describe it as being “on edge, keyed up, jumpy, things like that,” he said (Vogt).

Robert J. Lifton is a psychiatrist based at Yale University, argues that in the search to understand the soldiers’ traumatic stress reaction, doctors should focus on the death and destruction that actually took place and its related questions of meaning, rather than invoke the idea of “neurosis.”

Robert J. Lifton is a psychiatrist based at Yale University, argues that in the search to understand the soldiers’ traumatic stress reaction, doctors should focus on the death and destruction that actually took place and its related questions of meaning, rather than invoke the idea of “neurosis.”

“At the heart of the traumatic syndrome—and of the overall human struggle with pain—is the diminished capacity to feel, or psychic numbing. There is a close relationship between psychic numbing . . . and death-linked images of denial (‘If I feel nothing, then death is not taking place’), or ‘I see you dying but I am not related to you as your death.’”

Lifton tells us this happens in order for the soldier to avoid losing his sense completely and permanently. “He undergoes a reversible form of symbolic death in order to avoid a permanent physical or psychic death.”

Having closed off and numbed themselves in order to survive, soldiers are then faced with the task of working their way back toward humanity. The struggle is to “re-experience himself as a vital human being.” However, it is not all that easy, for “one’s human web has been all too readily shattered, and in rearranging one’s self-image and feelings, one is on guard against false promises of protection, vitality, or even modest assistance. One fends off not only new threats of annihilation but gestures of love or help.” (Bently)

A short survey conducted, in July 2010, showed that soldiers (currently deployed and those who have returned) would prefer group therapy lead by a trained leader. Also the survey stated that the soldiers would prefer not to be reliant on medication for depression, anxiety, sleeplessness (Waite).

Works Cited

“What Is PTSD? – National Center for PTSD.”National Center for PTSD Home. 14 June 2010. Web. 02 Aug. 2010

Knickerbocker, Brad. “PTSD: New regs will make it easier for war vets to get help.”Christian Science Monitor” 10 July 2010: N.PAG.Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 23 July 2010.

Bentely, Steve. “A Short History of PTSD: From Thermopylae to Hue Soldiers Have Always Had A Disturbing Reaction To War Article”. The Official Voice of Vietnam Veterans of America, Inc. 25 July 2010

Pols, Hans. “Waking up to shell shock: psychiatry in the US military during World War II.”Endeavour 30.4 (2006): 144-149.Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 25 July 2010.

Taylor, Rupert. “Understanding Battle Fatigue: Shell Shock Is Recognized as a Mental Illness Not Character Flaw.” Modern War. 24 Feb. 2009. Web. 25 July 2010.

Vogt, Heidi. “Army Keeping Traumatized Soldiers in Combat – Health – Mental Health – Msnbc.com.”Breaking News, Weather, Business, Health, Entertainment, Sports, Politics, Travel, Science, Technology, Local, US & World News- Msnbc.com. 1 Aug. 2010. Web. 02 Aug. 2010.

“Getting Care.”Welcome to TRICARE, Your Military Health Plan. 19 May 2010. Web. 02 Aug. 2010.

“NCMAF – How to Become a Chaplain.”Welcome to NCMAF / ECVAC. 16 May 2010. Web. 27 July 2010.

United States Senate Armed Services Committee. Hearing to receive testimony on military health system programs, policies, and initiatives in review of the defense authorization request for fiscal year 2011 and the future years. 24 March, 2010. United States Senate Armed Services Committee. Web. 23 July, 2010.

“Obama, Shinseki Cite Post Traumatic Stress as Priority.”Military Medicine (2009): 5-6. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 23 July 2010

Waite, B., “Questions for military personnel on mental health care.” Unpublished survey, 2010.

Rhetorical Rationale

Who was the target audience? Why did you choose that audience? (be specific)

US Citizens, military personnel and the US government. Because, it is an issue that needs to be addressed.

What did you hope to accomplish (what was your purpose) with your argument?

Colleges and the psychology associations in America will start putting forth the effort to teach how to use therapy rather than medicate for PTSD.

Describe your research experience. How did your opinions change and grow throughout the process? What challenges did you face? How did you overcome them?

No. I knew about my topic before I started it. I found out that my first opinion about the matter was true. There are other items I did not know, and was able to research the issues further. I found that the schools and TriCare do not really want to address the issue of finding Therapists to help military personnel rather than Psychiatrists who would rather treat with drugs.

What revisions did you make from the first draft to the final version? Why did you make those revisions? (be specific)

Added more information, fixed some fluidity and grammatical errors

What was the best peer advice you received for your argument essay? How did the peer review process help you become a better writer?

Make it more fluid. The advice made me focus better on blending my thoughts together.

What else would you like me/readers to know about you and your writing? (You may beg for mercy)

I understand cannot resolve the issue, but if enough Americans can see the same point of view and voice their opinions perhaps military personnel will get the therapy they truly deserve.

Writing this paper was very personal. It was not easy to deal with some of my own issues with PTSD, but it did help me understand the issues my friends that have served, are serving and will serve will face with their own PTSD. With the knowledge I have gained I hope will be able to help them. At least I will understand where they are coming from.

Argument Draft

Darren watches as the faces of friends fade in and out, his breath slow and ragged. He finishes off another beer and puts the can down next to an empty bottle of Jack and the nearly finished 24 pack. A bottle of pills, the doctor gave him, sit on the other side. Darren doesn’t remember how many he’s taken tonight. He doesn’t want to remember, doesn’t want to see the images again.

The nightmare begins nearly the same. Men huddled against a building, rifles in hand, fingers lightly on the triggers. The order comes to advance; each man takes slow cautious steps forward. Darren can hear the echoes of rifles going off in the distance. The earth shakes from a bomb hitting a building nearby. Darren looks back to see a new replacement looking around, scared. Darren offers a gesture of encouragement; he vaguely remembers what it was like to be green, the first time out, funny how 8 months can make such a big difference. The group is able to advance for two blocks before they’re commanded to halt. Before anyone could move a burst of bright lights, flying debris and the ground shakes again. The building next to them collapses. Rifle fire and commands fill the air. Darren’s mind becomes blank for a moment, just a second. He turns to find one of his friends, McFarson, lying on the ground, his face nearly gone. Darren moves to see if he’s still alive; before he touches his friend Darren already knows he’s dead. Darren’s head snaps to when he hears his name and a command to get moving. He starts ahead, only to remember the green replacement. He looks around to find the kid in pieces on the opposite wall. He gathers what encouragement he can find and moves closer to his commanding officer. Five of the 12, which started out, survived that day.

Darren looks down at his leg; his pants cover the wounds from the debris. He was lucky, they say. The wounds were only minor. “Lucky?” he retorts. “Lucky would have been dead with the rest, lucky is not coming home and loosing your wife and kids. Lucky isn’t having people look at you funny and call you baby killer when you walk the streets. I can’t even remember why I was so proud to wear the uniform.”

Darren wakes up only to find himself, not at home, but somewhere strange. He’s mind is in such a state that he really can’t focus to react. The nurses are all nice. The others that live there are a bit strange, but Darren’s mind is still too sedated to care.

Scenario sound familiar? It is a combination of many stories written by soldiers since the US Civil War.

Military history of treating PTSD in the US

Richard A. Gabriel, a consultant to the Senate and House Armed Services Committees and one of the foremost chroniclers of PTSD, tells us that in 1863 the number of insane soldiers simply wandering around was so great, there was a public outcry. Because of this, and at the urging of surgeons, the first military hospital for the insane was established in 1863. The most common diagnosis was nostalgia. The government made no effort to deal with the psychiatrically wounded after the war and the hospital was closed. There was, however, a system of soldiers’ homes set up around the country (Bentely).

During World War I, military officers encountered a new and puzzling phenomenon: soldiers emerged from the trenches stuttering, crying, trembling and at times were even paralyzed and blind. Those in charge were convinced these soldiers were cowards or malingerers who deserved stern discipline or to be court-martialled (Pols).

By World War II, psychiatrists were attached to many military units at the division level. Soldiers who were traumatized by witnessing extreme violence were pulled out of the front lines for treatment. This involved supportive counseling with the aim of getting them back to their fighting comrades within three days to a week (Taylor).

Modern aspects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Flashbacks, nightmares, depression, anxiety, removing yourself from activities you once enjoyed, becoming emotionally numb and difficulty maintaining close relationships are just some of the symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

The Department of Veterans Affairs Center for PTSD defines PTSD as: a psychiatric disorder that can occur following the experience or witnessing of life-threatening events such as military combat, natural disasters, terrorist incidents, serious accidents or violent personal attacks

The “Golden Hour”

Military medicine has come a long way from the days where a wounded soldier would never make it home to the now called “golden hour” where many soldiers are making it home. R Adams Cowley, M.D., explained in an interview: “There is a golden hour between life and death. If you are critically injured you have less than 60 minutes to survive. You might not die right then; it may be three days or two weeks later — but something has happened in your body that is irreparable.”

But is there a “golden hour” for those that are injured mentally?

Civil service agents, depending on departmental protocols, are removed from service to meet with a psychologist/psychiatrist after being involved with a shooting. Soldiers serving on the battle front do not have that luxury. Soldiers go through suicide and depression briefings before they are deployed and when they reach the country, in which they are deployed in, though they are never introduced to the mental health care provider or councilor. They are left to their own conscious to seek mental health care support. There is no mandatory protocol that states that a soldier must meet with a mental health care provider or group therapy session after any mission.

Speaking to commanding officers and non-commissioned officers if they are told that a soldier is feeling or showing suicidal or depression tendencies the soldier is put on suicidal watch and then taken to medical professionals. When deployed, if military personnel has issues with a situation there are psychologists, psychiatrists and pastoral councilors to help. When speaking to the soldier, most say that there is no professional help, save medical doctors or pastoral counselors, to talk to. Most soldiers do not seek help due to the stigma of having a mental disorder.

Robert J. Lifton is a psychiatrist based at Yale University, argues that in the search to understand the soldiers’ traumatic stress reaction, doctors should focus on the death and destruction that actually took place and its related questions of meaning, rather than invoke the idea of “neurosis.”

“At the heart of the traumatic syndrome—and of the overall human struggle with pain—is the diminished capacity to feel, or psychic numbing. There is a close relationship between psychic numbing . . . and death-linked images of denial (‘If I feel nothing, then death is not taking place’), or ‘I see you dying but I am not related to you as your death.’”

Lifton tells us this happens in order for the soldier to avoid losing his sense completely and permanently. “He undergoes a reversible form of symbolic death in order to avoid a permanent physical or psychic death.”

Having closed off and numbed themselves in order to survive, soldiers are then faced with the task of working their way back toward humanity. The struggle is to “re-experience himself as a vital human being.” However, it is not all that easy, for “one’s human web has been all too readily shattered, and in rearranging one’s self-image and feelings, one is on guard against false promises of protection, vitality, or even modest assistance. One fends off not only new threats of annihilation but gestures of love or help (Bently).”

Trends in treating Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Combination therapy would ideally result in better compliance and eventual completion of treatment programs provided for PTSD sufferers. Healthcare professionals strive to provide patients with holistic care. Patients present with unique mental and physical intricacies, and nurses and health professionals must peel away the layers to uncover the nature of the PTSD (Bastien).

One involves dogs specially-trained to assist veterans diagnosed with PTSD. Some of the dogs have been raised and trained by prison inmates through a program called “Puppies Behind Bars.” Horses also are being used as therapy animals for veterans.

The “Welcome Home Project” based in Oregon organized a retreat where recently-returned vets described their experiences through poetry, storytelling, and other art forms. The organization promotes community “welcoming ceremonies” for vets, and it’s producing a documentary film titled “Voices of Vets.”

Meanwhile, organizations of Vietnam veterans have been acting as “big brothers” helping Iraq and Afghanistan vets learn how to cope with PTSD. ( Knickerbocker)

The use of electronic communication to deliver health care at a distance has continued to gain popularity and widespread use in both the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and the Department of Defense (Nieves).

Government criteria for mental health care providors.

Chaplain

According to the National Conference on Ministry to the Armed Forces website:

The basic requirements to become an Active Duty, Reserve, Guard or Civil Air Patrol Chaplain include:

- Ecclesiastical endorsement (certifies experience and degree requirements meet the standards of the respective ecclesiastical group)

- Two years religious leadership consistent with clergy in applicant’s tradition (strongly recommended)

- United States citizenship (No dual citizenship)

- Bachelor’s degree (120 semester hours or 180 quarter hours)

- A graduate degree to include a minimum of 72 semester hours (or equivalent) from a qualifying (accredited) institution. Not less than 36 hours must be in theological/ministry and related studies, consistent with the respective religious tradition of the applicant. Endorsers are free to exceed the DoD standard per ecclesiastical requirements, but cannot go below the minimal DoD requirements, e.g. many endorsers specifically require the Master of Divinity degree

- Active Duty Chaplains:

- Army: Commissioned prior to age 40 (Age waiver availability may vary from year to year)

- Air Force and Navy: Commissioned and on active duty by age 42 (Some consideration may be made for prior service)

- Pass a military commissioning physical

- Pass a security background investigation

- Ability to work in the DoD directed religious accommodation environment.

TriCare (military personnel health care insurance)

On 24 March 2010, members of the US senate, Subcommitee on Personnel, and

Commitee on Armed Services gathered together to discuss the mental health care currently being issued to military personnel. The following quote is the statement of RADM Christine S. Hunter, USN, Deputy Director of Tricare Management Activity.:

Our efforts to reduce the stigma associated with seeking mental healthcare have been accompanied by an increase in providers to meet the growing demand. Together with the Surgeons General and our TRICARE contractors, we’ve added over 1900 providers to the military hospitals and clinics, and more than 10,000 added to the networks. Visits have increased dramatically, with 112,000 behavioral health outpatients now seen every week. In addition, servicemembers and their families can access the TRICARE Assistance Program for supportive counseling via Webcam from their homes, 24 hours a day.

College of Psychology Schools in the US

A survey conducted to university and colleges through the US came up with nearly the same conclusion. “I do not know of any researchers in our department who are specifically studying combat PTSD at this time (Waite).” If the issue of PTSD so prevalent, why is it not a main focus in teaching current and future mental health care providers?

Government

Obama said his fiscal 2010 budget, which includes the largest VA funding increase in 30 years, will help to confront PTSD and traumatic brain injuries in a “more robust way.” “Throwing money at the problem by itself is not enough,” he conceded. But, he added, money does help by funding more counselors, mental health specialists and treatment facilities. “We’re hiring mental health providers,” Shinseki pointed out. “We’re up to 18,000 in the VA today (Obama, Shinski)”

Conclusion

A short survey conducted in July 2010 showed that soldiers currently deployed and those who have returned would prefer group therapy lead by a trained leader. Also the survey stated that the soldiers would prefer not to be reliant on medication for depression, anxity, sleeplessness or PTSD.

There is a concern within the Senate and the Commitee on Armed Services as well as the nation that our troops are relying on drugs that supress depression and anxiety, but there is not one specific method they choose to help those with PTSD.

Works Cited

Bentely, Steve. “A Short History of PTSD: From Thermopylae to Hue Soldiers Have Always Had A Disturbing Reaction To War Article”. The Official Voice of Vietnam Veterans of America, Inc. 25 July 2010

Pols, Hans. “Waking up to shell shock: psychiatry in the US military during World War II.”Endeavour 30.4 (2006): 144-149.Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 25 July 2010.

Taylor, Rupert. “Understanding Battle Fatigue: Shell Shock Is Recognized as a Mental Illness Not Character Flaw.” Modern War. 24 Feb. 2009. Web. 25 July 2010.

“R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center. Tribute to R Adams Cowley, M.D.” University of Maryland Medical Center. 10 Nov. 2009. Web. 26 July 2010.

NCMAF – How to Become a Chaplain.” Welcome to NCMAF / ECVAC. 16 May 2010. Web. 27 July 2010.

Waite Survey July 2010

“Obama, Shinseki Cite Post Traumatic Stress as Priority.” Military Medicine (2009): 5-6. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 23 July 2010

Thesis Statement RJ2

The U.S. government is not ensuring that military personnel have access to professionals properly trained in combat related mental health care.

Argument Paper Outline RJ2

Intro (story)

Define PTSD (per military and psychology stand-points)

Military history of treating PTSD

-Civil War

-WW I and WWII

-Korean and Vietnam War

-Middle Eastern War

Golden Hour (health care on the battle front)

-What is the “golden hour”

-Mental issues that occur when on the battle front

-Trends within mental health care

Health care at home

-What is the standards for psychiatrists treating soldiers

-tele

Conclusion

Research Reflection RJ2

Where did you find your source?

Online, interviews and emails.

In your search for sources, did you encounter many possible sources or just a few? Based on how many sources you found, do you think your research question is on the right track? Is it too broad? Too narrow? How might you refine it?

There is many journals, magazines etc articles being written about the topic, but so far I have yet to read anything to help the soldier just after an incident happens. I did not have problems researching the point I am trying to make.

What did you learn from your sources? Did you learn anything that surprised you or particularly interested you?

The one interview with the police officer did surprise me. I thought that all Civil Service personnel had to go into speak to a mental health care provider after a shooting incident. That is determined by the department.

I found that some the “top 10” psychology schools in the nation do not teach or research PTSD, combat or abusive.

How has your understanding and/or opinion about your topic changed or expanded?

I have learned how much the government has looked away from the topic of PTSD as well as the US psychology circles.

What new questions do you have about your topic?

What types of treatments really work? Why has the options for mental health care become so impersonal (telemental healthcare)? If PTSD (combat and abusive) is a large topic, why has it been researched in depth? There are many Vietnam, Korean and Middle Eastern veterans still alive, why are they not being used for in depth research on PTSD?

How do you think you can incorporate these particular sources into your argument essay?

By showing that since written accounts, have been available, there has been little research or care for a soldier’s mental health after battle.

Where do you plan to go from here? What types of other sources do you want to look for and where?

Making a few more phone calls to see if I can get more answers.

Audience Analysis RJ2

Who is the audience (be as specific as possible)?

US citizens

How will you capture their attention?

The topic of how bad off soldiers are with PTSD, but they have no idea what kind of mental health care military personnel are getting.

What are their current beliefs about the topic?

Mixed feelings about how the soldiers are being treated, or that they deserve it for even going out to the Middle East.

What are their relevant values?

Depends on the person you’re speaking to.

How will you convince them?

Showing them what kind of treatment the soldiers are getting or not getting.

Thesis Statement Peer Review RJ2

What patterns can you see in the thoughts of your peers about your thesis statement?

That they wondered why military personnel were not being taken care of in a decent manner. And that I need to find a different way of saying “professionals properly trained”, they said it seemed redundant.

What opportunities do you see in the peer responses to your thesis statement?

Both wondered what they could do to help.

Based on the peer responses, what is lacking in your thesis statement (what additional information is needed)? How will you address that issue?

I should re-word the statement. And how can I make such a bold statement.

Are there any problems with your thesis statement? What are they and how will you address them?

I am sure there are going to be many problems. The government has a lot of programs out there. The soldiers are saying that the top commanders are saying that if you have a problem go get it fixed, but when they C.O.s and N.O.C.s find out it becomes a problem, possible demotions, issues that you can’t “suck” it up, etc. And from the public which is at odds with if the US should be involved in the Middle Eastern conflict to begin with.

-

Archives

- August 2010 (4)

- July 2010 (15)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS